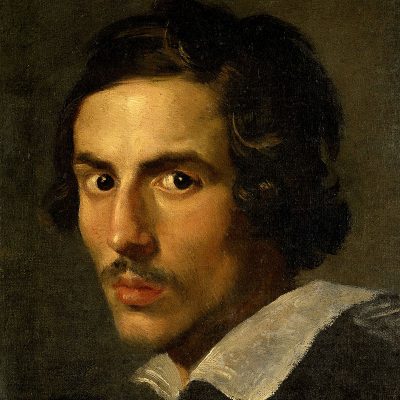

Gian Lorenzo (or Gianlorenzo) Bernini (UK: /bɛərˈniːni/, US: /bərˈ-/, Italian: [ˈdʒan loˈrɛntso berˈniːni]; Italian Giovanni Lorenzo; 7 December 1598 – 28 November 1680) was an Italian sculptor and architect. While a major figure in the world of architecture, he was more prominently the leading sculptor of his age, credited with creating the Baroque style of sculpture. As one scholar has commented, “What Shakespeare is to drama, Bernini may be to sculpture: the first pan-European sculptor whose name is instantaneously identifiable with a particular manner and vision, and whose influence was inordinately powerful …”[1] In addition, he was a painter (mostly small canvases in oil) and a man of the theater: he wrote, directed and acted in plays (mostly Carnival satires), for which he designed stage sets and theatrical machinery. He produced designs as well for a wide variety of decorative art objects including lamps, tables, mirrors, and even coaches.

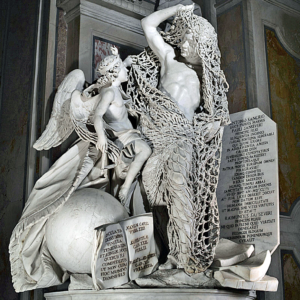

As an architect and city planner, he designed secular buildings, churches, chapels, and public squares, as well as massive works combining both architecture and sculpture, especially elaborate public fountains and funerary monuments and a whole series of temporary structures (in stucco and wood) for funerals and festivals. His broad technical versatility, boundless compositional inventiveness and sheer skill in manipulating marble ensured that he would be considered a worthy successor of Michelangelo, far outshining other sculptors of his generation. His talent extended beyond the confines of sculpture to a consideration of the setting in which it would be situated; his ability to synthesize sculpture, painting, and architecture into a coherent conceptual and visual whole has been termed by the late art historian Irving Lavin the “unity of the visual arts”.[2]

Under the patronage of the extravagantly wealthy and most powerful Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the young Bernini rapidly rose to prominence as a sculptor. Among his early works for the cardinal were decorative pieces for the garden of the Villa Borghese, such as The Goat Amalthea with the Infant Jupiter and a Faun. This marble sculpture (executed sometime before 1615) is generally considered by scholars to be the earliest work executed entirely by Bernini himself.[11] Among Bernini’s earliest documented work is his collaboration on his father’s commission of February 1618 from Cardinal Maffeo Barberini to create four marble putti for the Barberini family chapel in the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle, the contract stipulating that his son Gian Lorenzo would assist in the execution of the statues.[12] Also dating to 1618 is a letter by Maffeo Barberini in Rome to his brother Carlo in Florence, which mentions that he (Maffeo) was thinking of asking the young Gian Lorenzo to finish one of the statues left incomplete by Michelangelo, then in possession of Michelangelo’s grandnephew which Maffeo was hoping to purchase, a remarkable attestation of the great skill that the young Bernini was already believed to possess.[13]

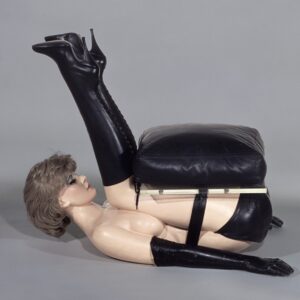

Although the Michelangelo statue-completion commission came to naught, the young Bernini was shortly thereafter (in 1619) commissioned to repair and complete a famous work of antiquity, the sleeping Hermaphrodite owned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese (Galleria Borghese, Rome) and later (circa 1622) restored the so-called Ludovisi Ares (Palazzo Altemps, Rome).[14]

Also dating to this early period are the so-called Damned Soul and Blessed Soul of circa 1619, two small marble busts which may have been influenced by a set of prints by Pieter de Jode I or Karel van Mallery, but which were in fact unambiguously cataloged in the inventory of their first documented owner, Fernando de Botinete y Acevedo, as depicting a nymph and a satyr, a commonly paired duo in ancient sculpture (they were not commissioned by nor ever belonged to either Scipione Borghese or, as most scholarship erroneously claims, the Spanish cleric, Pedro Foix Montoya).[15] By the time he was twenty-two, Bernini was considered talented enough to have been given a commission for a papal portrait, the Bust of Pope Paul V, now in the J. Paul Getty Museum.

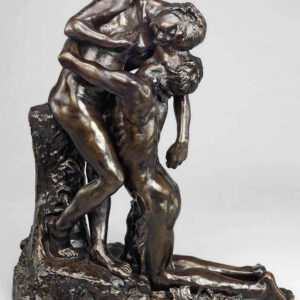

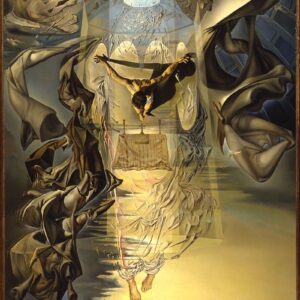

Bernini’s reputation, however, was definitively established by four masterpieces, executed between 1619 and 1625, all now displayed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome. To the art historian Rudolf Wittkower these four works—Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius (1619), The Rape of Proserpina (1621–22), Apollo and Daphne (1622–1625), and David (1623–24)—”inaugurated a new era in the history of European sculpture”.[16] It is a view repeated by other scholars, such as Howard Hibbard who proclaimed that, in all of the seventeenth century, “there were no sculptors or architects comparable to Bernini”.[17] Adapting the classical grandeur of Renaissance sculpture and the dynamic energy of the Mannerist period, Bernini forged a new, distinctly Baroque conception for religious and historical sculpture, powerfully imbued with dramatic realism, stirring emotion and dynamic, theatrical compositions. Bernini’s early sculpture groups and portraits manifest “a command of the human form in motion and a technical sophistication rivaled only by the greatest sculptors of classical antiquity.”[18] Moreover, Bernini possessed the ability to depict highly dramatic narratives with characters showing intense psychological states, but also to organize large-scale sculptural works that convey a magnificent grandeur.[19]

Unlike sculptures done by his predecessors, these focus on specific points of narrative tension in the stories they are trying to tell: Aeneas and his family fleeing the burning Troy; the instant that Pluto finally grasps the hunted Persephone; the precise moment that Apollo sees his beloved Daphne begin her transformation into a tree. They are transitory but dramatic powerful moments in each story. Bernini’s David is another stirring example of this. Michelangelo’s motionless, idealized David shows the subject holding a rock in one hand and a sling in the other, contemplating the battle; similarly immobile versions by other Renaissance artists, including Donatello’s, show the subject in his triumph after the battle with Goliath. Bernini illustrates David during his active combat with the giant, as he twists his body to catapult toward Goliath. To emphasize these moments, and to ensure that they were appreciated by the viewer, Bernini designed the sculptures with a specific viewpoint in mind. Their original placements within the Villa Borghese were against walls so that the viewers’ first view was the dramatic moment of the narrative.[20]

The result of such an approach is to invest the sculptures with greater psychological energy. The viewer finds it easier to gauge the state of mind of the characters and therefore understands the larger story at work: Daphne’s wide open mouth in fear and astonishment, David biting his lip in determined concentration, or Proserpina desperately struggling to free herself. In addition to portraying psychological realism, they show a greater concern for representing physical details. The tousled hair of Pluto, the pliant flesh of Proserpina, or the forest of leaves beginning to envelop Daphne all demonstrate Bernini’s exactitude and delight for representing complex real world textures in marble form.[21]